Laparoscopic Subtotal Hysterectomy

Authors

INTRODUCTION

Hysterectomy is the second (after cesarean section) most commonly performed major surgery in the United States. Approximately 600,000 hysterectomies are performed in the United States annually, and the number remains fairly constant.1, 2 Most hysterectomies are abdominal, and the most common indications are uterine leiomyomas and dysfunctional uterine bleeding. In the 1990s, laparoscopic hysterectomy emerged as an alternative to the traditional abdominal or vaginal hysterectomy. Because of its various benefits (less morbidity, less bleeding, less tissue damage, short hospital stay, quick recovery, and better cosmetic results), laparoscopic hysterectomy has attracted considerable attention. Three main types have been described: laparoscopic hysterectomy, laparoscopic subtotal (supracervical) hysterectomy (LSH), and laparoscopic-assisted vaginal hysterectomy. The first two are performed exclusively through the laparoscopic approach. Laparoscopic-assisted vaginal hysterectomy is a vaginal hysterectomy preceded by laparoscopic isolation of the adnexa and variable degrees of dissection classified into stages.3

Reports describing techniques of performing LSH and various terms coined to label it have been published. The same basic technique was described by Lyons4 as laparoscopic supracervical hysterectomy, by Hasson and colleagues5 as supracervical laparoscopic hysterectomy, and by Donnez and colleagues6 as laparoscopic assisted supracervical hysterectomy. An intrafascial cervix coring technique was described by Metler and coworkers7 initially as classic abdominal Semm hysterectomy and subsequently as classic intrafascial supracervical hysterectomy (CISH).7 It also was labeled pelviscopic intrafascial hysterectomy by Vietz and Ahn.8 Sadoghi9 described a transvaginal approach, and Pelosi and Pelosi10 reported a single-puncture technique. The American Association of Gynecologic Laparoscopists, in an effort to standardize the terminology, used the term laparoscopic subtotal hysterectomy (LSH) to describe any laparoscopic procedure in which the uterine corpus is removed and the cervix or any portion thereof is retained.3A new recently evolving approach is the robotic-assisted hysterectomy with the da Vinci surgical system. Approved by the Federal and Drug Administration in 2005 for gynecological surgery, this new technique has advantages and disadvantages, and experience is still at an early stage.11, 12, 13 To our knowledege no studies have been done using this new technique for subtotal hysterectomy.

HISTORICAL BACKGROUND

Before 1940, 95% of all hysterectomies performed in the United States were subtotal.14 The cervix was left behind to minimize morbidity, especially as it related to ascending infection from the vagina. In the mid-1940s, with the advent of penicillin and the increased availability of blood transfusions, total abdominal hysterectomy (TAH) began to gain popularity. Improvements in anesthesia and electrolyte management also helped improve outcomes. With scientific data estimating the incidence of carcinoma of the cervical stump at 1% to 2%,15, 16 practitioners sought to prevent this cancer by removing the cervix with the uterus. Subtotal (supracervical) hysterectomy started to decline, and TAH became the standard of care. In Los Angeles in the 1940s, 64% of the hysterectomies were subtotal; in the 1950s, 29% were subtotal; and by 1975, only 5% were subtotal.14 The rate of subtotal hysterectomy reached its lowest point in the early 1990s (0.7%)1 but increased eightfold over the subsequent 13 years to 5.6% by 2003.2

In 1942, Papanicolaou17 introduced a technique for the examination of cervical cells that provided a highly effective screening test for cervical cancer (Papanicolaou [Pap] smear). By the time this cytologic screening method was accepted, however, the switch from subtotal to total hysterectomy had taken place.

Since the introduction of laparoscopic hysterectomy by Reich and colleagues in 1989,18 the total number of TAHs performed annually has slowly declined. Between 19901 and 20032 the percentage of TAH declined from 73.6%1 to 61.6%.2 During the same period, laparoscopic hysterectomies increased from 0.3%1 to 11.8%,2 with the most common reason for performing hysterectomy of any type being uterine fibroids. Similar trends have been seen in the Netherlands,19 Finland,20 the Czech Republic,21 Australia,22 and Denmark.23 In addition to laparoscopic innovations, less invasive alternative approaches have been developed for the treatment of leiomyomas and dysfunctional uterine bleeding, including medical therapies, abdominal, laparoscopic or hysterosopic myomectomy, uterine artery embolization, magnetic resonance imaging-guided focused ultrasound surgery, and various types of endometrial ablation procedures.24, 25

RISKS OF RETAINING THE CERVIX

Other than the force of habit and tradition, the major reason for removing the cervix at the time of hysterectomy for benign disease is fear of cancer development in the cervical stump. To evaluate this risk, one needs to consider the incidence of such occurrence and whether removal of the cervix would eliminate it.

The incidence of cervical stump carcinoma is low, and such occurrences are often preventable if the established guidelines are followed.26, 27, 28 Among 1104 women who underwent supracervical hysterectomy for benign conditions, only 0.2% developed cervical stump carcinoma during 10 years of observation.29 Kilkku and Gronroos followed 2712 women who underwent subtotal hysterectomy between 1958 and 1978. They reported an incidence of cervical stump carcinoma of 0.11%.30 These rates are not significantly different from the 0.17% incidence of vaginal cuff cancer after TAH.31

Carcinoma of the cervical stump may be divided into two distinct groups: coincidental cases and true cases. Coincidental cases are detected within 2 years after hysterectomy and are considered to be due to pre-existing disease that escaped detection at the time of hysterectomy. True cases are detected later and considered to have arisen de novo in the stump.32 Most cervical stump carcinomas are of the squamous cell type (87.6–91%); adenocarcinomas account for the remainder.33, 34 The long-term prognosis for radiologically treated squamous cell carcinoma of the uterine stump is similar to that of cervical carcinoma with an intact uterus. The prognosis for stump adenocarcinoma is worse, however. The mean time interval from procedure to diagnosis of cervical stump carcinoma was 17.6 years.33 This delay in diagnosis may be due to reduced frequency of Pap smear screening.

Recent microbiologic tests show high correlation (99.7%) between human papillomavirus (HPV) and cervical dysplasia.35 HPV types 16 and 18 have been recognized as highly carcinogenic subtypes. HPV type 16 is associated mainly with squamous differentiation, whereas HPV type 18 is associated mainly with adenosquamous differentiation. Two longitudinal Swedish studies measured the HPV type 16 viral load in multiple Pap smears from women taken over periods up to 26 years. Elevated levels of HPV type 16 predicted a high probability of the development of cervical cancer, even when cervical cytology was completely normal.36, 37

Such data seem to indicate that prophylactic removal of the cervix does not eliminate the risk of cancer, but rather shifts that risk to the vaginal epithelium in high-risk patients. Kalogirou and colleagues38 followed 793 patients with previous history of total hysterectomy. During 10 years of observation, they found that 41 patients (5%) developed vaginal intraepithelial neoplasia (VaIN). Other clinical observations have implicated HPV in the development of VaIN.39, 40 Women who have a hysterectomy for benign reasons but who are known to be infected with carcinogenic subtypes of HPV may be at higher risk for VaIN and should be followed appropriately. Numerous studies have reported cases of VaIN III and vaginal carcinoma after hysterectomy for benign disease.38, 41 More recently it has been reported that 80–90% of anal cancers are associated with HPV 16 or 18,42 and up to 40% of vulvar cancers are HPV-related.43

Another problem with total hysterectomy is sequestration of vaginal epithelium above the suture line from improper cuff closure or healing. Should atypical epithelium develop in these inaccessible locations, it may not be available for cytologic screening or colposcopic evaluation and may progress to invasive cancer before being detected.32, 44

INTRODUCTION OF HPV VACCINE: A NEW ERA

In the United States genital human papillomavirus is the most commonly sexual transmitted infection. Approximately 6.2 million persons are newly infected every year, the majority being self-limited, but if persistent the infection may progress to cervical cancer, and other types of anogenital diseases.45, 46, 47, 48

Currently, an estimated 20 million people in the United States are infected with HPV. Almost half of the infections are in those aged 15–25 years. The prevalence of HPV is 27–46% in young women. At least half of all sexually active women and men acquire HPV at some point in their lifetime by age 50. In the United States up to 90% of genital warts are associated with HPV 6 or 11.47, 48

More than 100 HPV types have been identified, over 40 of which infect the genital area. Roughly 15 carcinogenic types cause virtually all cervical cancer worldwide.49, 50 Most HPV infections are transient and asymptomatic, 70% of new infections clear within 1 year, and around 90% clear within 2 years. The most important factor for the progression to precancerous lesion or invasive cervical carcinoma is a persistent infection with high-risk HPV type, HPV 16 being the most oncogenic.51 One study found the prevalence of HPV 16 was 13.3% among ASC-US, 23.6% among LSIL, and 60.7% among HSIL Pap test.52 In another reported study, HPV 16 and 18 were found in approximately 68% of squamous cell carcinoma, and 83% of adenocarcinoma of cervix.48

The American Cancer Society predicts 11,070 new cases of cervical cancer will occur in 2008 and that 3870 women will die from this disease the same year.53 The stepwise progression from HPV acquisition to invasive cancer takes 20 years on average, although there are cases that develop more rapidly.54 This slow development allows for ample opportunity to detect the precancer state and treat it.

Since the introduction of Pap testing in the 1950s, the incidence of cervical cancer rates has decreased by approximately 75%, and death rates approximately 70% primarily in squamous cell carcinomas; the incidence of adenocarcinomas has not changed appreciably, mainly because its endocervical location makes of it more difficult to detect.48

In June 2006 a quadrivalent HPV vaccine (GardasilTM, produced by Merck and Co, Inc.) against types 6, 11, 16, and 18 was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for use in females aged 9–26 for the prevention of vaccine HPV-type-related cervical cancer, cervical cancer precursors, and anogenital warts. It is administered intramuscularly at 0, 2, and 6 months. Little information is available on the duration of HPV-induced immunity to determine if a booster is recommended.47, 48, 55 Since its introduction, it has been approved in 85 nations.

BENEFITS OF RETAINING THE CERVIX

Sparing the cervix at the time of performing hysterectomy may have advantages, including less surgical trauma and blood loss, fewer incidences of vaginal vault prolapse, enterocele, and vaginal shortening. Beneficial effects of retaining the cervix on the neurophysiologic status of the pelvic organs and the psychosexual behavior of the patient have been suggested32 but not proven.56

NORMAL ANATOMY AND PHYSIOLOGY

The endopelvic fascia is a continuous layer of connective tissue that surrounds each pelvic organ and spreads to the pelvic side walls, where it attaches to the parietal fascia. Medially the endopelvic fascia forms two main supportive pelvic ligaments, the cardinal and uterosacral ligaments, which hold the cervix and the vagina in place. Approximately two-thirds of these supporting ligaments attach to the cervix (cardinal ligaments) and one-third to the vagina (upper paracolpium); the rest of the uterus is freely mobile. The round ligaments, which attach the upper part of the uterus to the pelvic wall, are thin and play a minor role in uterine support and position.57, 58 The proximal third of the vagina is supported by a well-defined paracolpium, which becomes less defined in the middle third and indistinct in the distal third. In its most caudal part, the vagina is fused with the surrounding structures without an intervening paracolpium.59

The cervix and upper vagina are intimately associated with the paracervical plexus and ganglia (Frankenhäuser plexus), which is the major relay station of all autonomic and sensory neurotransmissions from the pelvic organs, upper vagina, bladder, and proximal urethra. The bulk of this plexus consists of ganglia that lie below the broad ligament within the cardinal ligaments on each side of the cervix and upper vagina in front of the rectum.60, 61 Sensory nerve fibers from the cervix, upper vagina, and proximal urethra pass through the Frankenhäuser plexus and pelvic nerves to the second, third, and fourth sacral nerves. Sensory nerves of the lower vagina, perineum, and distal urethra pass primarily through the pudendal nerve.57, 59, 60

POTENTIAL PROBLEMS OF TOTAL HYSTERECTOMY

Anatomic

SURGICAL INJURY.

In total hysterectomy, the bladder is mobilized and dissected from the cervix and the main trunk of the uterine artery, which is closely related to the ureter. These steps are associated with an increased risk of urologic injury.41, 62, 63 The increased dissection also may be associated with increased blood loss.

VAGINA VAULT PROLAPSE AND ENTEROCELE.

Vagina vault prolapse and enterocele are common after TAH or total vaginal hysterectomy.64

VAGINAL SHORTENING.

Jewett65 measured the vaginal depth immediately before and 6 weeks after surgery. He found that 12% of patients showed vaginal shortening after TAH.

IMPROPER CLOSURE OF THE VAGINAL CUFF.

Improper closure can lead to abnormal granulation tissue or tissue sequestration as previously discussed,32, 44 and vesicovaginal fistula.

RARE COMPLICATIONS.

Prolapse of the preserved fallopian tubes is a rare complication, with 80 cases reported in the literature.66 Vaginal vault rupture and intestinal herniation are other complications, with several cases reported.64

Neurophysiologic Concerns

Cervical amputation may damage the paracervical plexus, causing anorectal and urethrovesical dysfunction. Several clinical studies support this concept.67, 68, 69 The evidence to date is conflicting, however.70

Psychosexual Concerns

Different women experience orgasm differently, by clitoral or vaginal stimulation, or a combination of both. Some other women feel that pressure against the cervix during intercourse is pleasurable and is important to their sexual experience. Despite there being no objective evidence of a benefit to subtotal hysterectomy, some post-hysterectomy patients noticed a benefit from retaining the cervix.

The cervix has few pain receptors; however, it has many pressure and temperature receptors, which may be stimulated with light pressure via the lateral vaginal fornices, eliciting pleasurable sensation.60 Loss of a major portion of the paracervical plexus, through excision of the cervix and extensive dissection, may alter a woman’s sexual response.32 Some studies support this concept.71, 72, 73 Other studies have failed, however, to show a difference in sexual response between total, vaginal, and subtotal CISH or subtotal abdominal hysterectomy.74, 75 Grimes76 reviewed the pertinent literature and concluded that the evidence for and against a role for the cervix is weak.

Thakar analyzed the sexual function of 279 patients undergoing total or subtotal hysterectomy. The desire, initiation, frequency of intercourse was not different prior to surgery or at 6–12 months follow-up among the two groups. Deep dyspareunia was reduced, and frequency of intercourse increased in both groups.56 In another clinical study, Kupermann assigned 135 patients to either total or subtotal hysterectomy. He noticed a higher score on the frequency of orgasm and quality of life at 6 months for the subtotal group; he also noticed that this initial diference dissipated at 2 years. This difference at 6 months could have been related to initially different baseline sexual problems.77

Another important function of the cervix in premenopausal women is to contribute to the vaginal lubrication at the time of intercourse.78 Decreased lubrication is a well-recognized cause of dyspareunia. Jewett65 implicated vaginal shortening, as a consequence of total hysterectomy, as a cause of dyspareunia.

INDICATIONS AND CONTRAINDICATIONS FOR LAPAROSCOPIC SUBTOTAL HYSTERECTOMY

The indications for LSH are identical to those for abdominal hysterectomy for benign disease. The contraindications include the following:

- Patient’s medical condition or certain degree of obesity makes it inadvisable to keep the patient in Trendelenburg position with a pneumoperitoneum for a prolonged period.

- Uterine size greater than 18 weeks’ gestation.

- Malignant or premalignant lesions of the cervix, including persistent or recurrent high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions.

- Malignant or premalignant lesions of the endometrium, including atypical adenomatous hyperplasia.

- Adequate follow-up is not anticipated.

- Patient desires gender reassignment.

SPECIAL SITUATIONS

Cervical Dysplasia

Low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions are not a contraindication for LSH, provided that adequate follow-up and treatment are provided. Most patients with this associated condition may prefer total laparoscopic hysterectomy, however.

Obesity

The incidence of obesity in the United States has increased dramatically over the past 20 years. The World Health Organization and the National Institute of Health define normal weight as body mass index (BMI) of 18.5–24.9, overweight as BMI of 25–29.9, and obesity as BMI 30 or greater. The most recent National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) for 1999–2002 found that approximately one-third of adult women in the United States are obese.79 Sooner or later the gynecologic surgeon is going to encounter one of these patients. The most important technical difficulty when doing laparoscopic surgery in obese patients is establishing pneumoperitoneum. The abdominal wall is thick, the preperitoneal and retroperitoneal fat is abundant and the omentum is large, leaving little room to operate. When in Trendelenburg's position, the weight of the bowel and omentum increase the airway pressure, making ventilation difficult. Despite these challenges, the laparoscopic approach is recommended in obese patients since these patients are more succeptible to thrombotic events due to less mobility, and they have increased risk for suboptimal wound-healing when having a laparotomy.

Two studies evaluated the feasibility of total laparoscopic hysterectomy in obese patients. O'Hanlan and co-workers evaluated 330 women who had laparoscopic hysterectomy and grouped them by BMI. They noted that the mean operative times, estimated blood loss, length of hospital stay, and major and minor complication rates were no different among the ideal body weight, overweight, or obese groups. In addition, the complication rates were similar across all BMI groups, concluding that this technique is feasible and safe in this population. O'Hanlan also reported that the operative time decreased with more laparoscopic surgical experience.80 In another clinical observation, Heinberg analyzed 270 women following total laparoscopic hysterectomy, 106 of whom had a BMI above 30. They reported that 6.6% in the obese group were converted to laparotomy versus 1.8% in the non-obese group. Although obese women had longer operative times (133 vs. 114 min) and blood loss (240 vs. 178 ml), there were no differences in major or minor complication, hospital readmissions, or need for reoperation. They also noted fewer conversions to laparotomy as operator experience accrued.81

LSH may be offered to women who are obese, and thus may avoid the risk of post-operative complications associated with the abdominal incision and mobilization. To our knowledge, no study has evaluated LSH in obese patients.

PREOPERATIVE PREPARATION

The procedure is explained to the patient, and informed consent is obtained. Preoperative workup includes a normal Pap smear obtained within 1 year and a recent ultrasound of the pelvis. Endometrial biopsy is recommended for patients with abnormal endometrial thickening found on ultrasound. Preoperative medical therapy is used to reduce the size and vascularity of the uterine mass and to conserve menstrual blood loss before surgery, as indicated. Prophylactic antibiotics and bowel preparation also are recommended.

SURGICAL TECHNIQUE

Preparation

After adequate anesthesia, the patient is placed into Allen stirrups with the thighs roughly parallel to the floor and the heels comfortably resting on the foot rests. The patient’s toe, knee, and opposite shoulder are aligned in a straight line. The bladder is emptied, and a Foley catheter is left indwelling. An appropriate uterine manipulator is used to mobilize the uterus.

Access and Exploration

Our team uses the open laparoscopy approach for primary access and three secondary access points drawn along the line of an imaginary Pfannenstiel incision for manipulation. Exploration of the pelvis and abdomen is the first step in the operation. This includes systematic exploration of the upper abdomen, the diaphragm, liver and gallbladder, appendix, omentum, pelvic organs, and cul-de-sac. After exploration, the uterus and adnexa are freed from adhesions if present.

Anterior Dissection and Development of the Bladder Flap

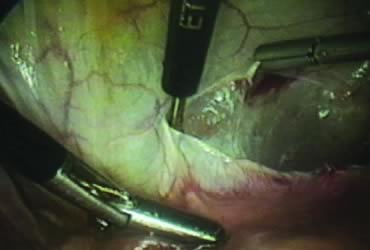

The right round ligament is held in its midportion, coagulated with bipolar forceps, and cut (Fig. 1). The anterior leaf of the right broad ligament is incised parallel to the uterus, and the incision is curved medially over the cervix (Fig. 2). The same two steps are repeated on the left side, and the incisions are connected (Fig. 3). The bladder flap is mobilized out of the surgical field by cutting the cervicovaginal septum, as needed. Coagulation and cutting the superficial upper portions of the lateral vesicouterine ligaments or bladder pillars completes the dissection.

Posterior Dissection

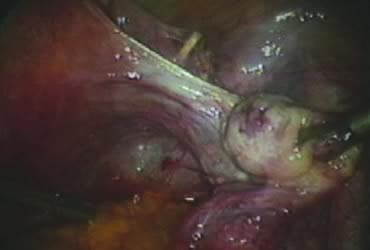

The right ovary is held with the three-prong grasper stretching and exposing the utero-ovarian ligament, which is coagulated and cut in its midportion (Fig. 4). The posterior leaf of the right broad ligament is incised downward to the level of the insertion of the uterosacral ligament in the cervix. The same two steps are repeated on the opposite side and the two sides are connected (Fig. 5).

Isolation of the Adnexa

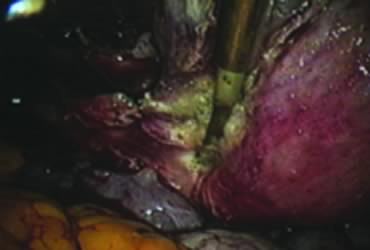

A window is created in an areolar avascular area of the broad ligament with gentle blunt dissection. The adnexal structures above the window are coagulated (or sutured) and cut, isolating the adnexa and detaching it from the uterus (Fig. 6). The procedure is repeated in the contralateral side.

Securing Uterine Vessels

In supracervical hysterectomy, only the ascending branch of the uterine artery is skeletonized and secured preferably with a stitch (Fig. 7). The tissues medial to the stitch are coagulated (to prevent back flow) and cut (Fig. 8). The same steps are repeated on the opposite side.

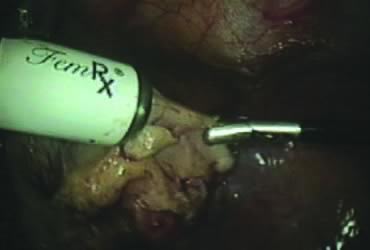

Amputation of the Uterus and Ablation of the Endocervix

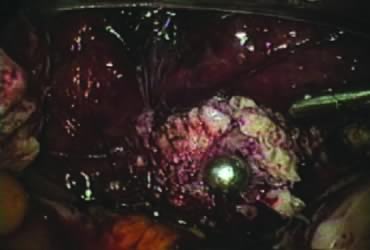

After ligating both uterine arteries, the uterus becomes pale. At this time, the uterine body may be divided longitudinally using a shielded knife down to the cervix to facilitate morcellation. Each half is detached separately from the cervix 0.5–1 cm below the uterocervical junction and stored in the left upper abdomen. Alternatively, amputation of the uterine body off the cervix may be carried out through coagulation and cutting (above the ligated artery) proceeding from lateral to medial. The process may be initiated from the right or the left side. Bleeding points in the cervical stump are secured (Fig. 9). The upper portion of the endocervical canal is ablated circumferentially with bipolar coagulation (Fig. 10). Initially the walls of the cervix and the edges of the peritoneum were drawn together with sutures. This step was omitted, however, after noting at second look that the pelvic peritoneum heals without adhesions in the absence of sutures.

Concomitant Adnexectomy

If indicated, salpingo-oopherectomy can be performed at this time.

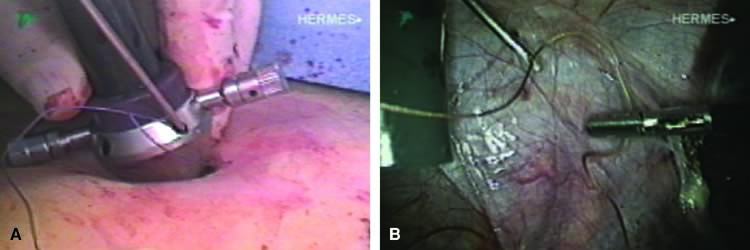

Removal of the Specimen

The stored uterus is removed using a mechanical morcellator, which is essentially a circular rotatory knife that slices the tissues longitudinally in the shape of a cylinder. The incision in the left lower quadrant is increased to 17 mm to accommodate a 15-mm trocar. The secure cone is mounted over the trocar, which is inserted into the abdomen.82 Sutures are passed through the tunnels of the secure cone to hold and stabilize the cannula in place (Fig. 11A). The mechanical morcellator is introduced through the 15-mm cannula, and morcellation is carried out in horizontal fashion by pulling the tissues into the morcellator from right to left to minimize the possibility of bowel injury (Fig. 12). When morcellation is complete, the trocar and the cone are removed, leaving the stay sutures in place. Tying these sutures together closes the surgical defect in the abdominal wall (Fig. 11B).82

Lavage, Inspection, and Closure

The pelvic cavity is irrigated, the operative sites are inspected, and small bleeding points are controlled, if needed. The enlarged incision in the left lower quadrant is closed under direct vision, as previously described. Secondary access trocars are removed under direct vision. The abdomen is deflated, and the primary access cannula is withdrawn. The open laparoscopy incision is closed in layers. The Foley catheter and the uterine manipulator are removed, and the operation is completed.

CLASSIC INTRAFASCIAL SUPRACERVICAL HYSTERECTOMY TECHNIQUE

In the CISH technique, after the uterine body is amputated, the endocervical canal is cored out, and the transformation zone of the cervix is resected.

CLINICAL EXPERIENCE

Tables 1 and 2 show selected studies83, 84, 85, 86 and outcome data for the LSH and CISH procedures. In reviewing the first 100 cases of LSH performed by our team, the average estimated blood loss was less than 100 ml with no blood transfusions given. The operative time ranged from 60 to 180 minutes; the mean length of stay was 1 day. Five patients complained of postoperative cyclic bleeding: Two of these experienced spontaneous cessation within a few months, two continued with scanty menses that did not cause them concern, and one had her cervix removed vaginally. Histology revealed endometriosis. Another patient had cervicectomy because of an abnormal Pap smear; histology revealed chronic cervicitis without dysplasia.

Table 1. Comparison of outcomes of laparoscopic subtotal hysterectomy and classic intrafascial supracervical hysterectomy procedures from selected studies

Procedure | Author | No. patients | ORT (min) (range) | EBL (mL) (range) | LOS (h) (range) |

LSH | Donnez83 | 500 | 62 (30–135) | <100 | 42–72 |

Lyons84 | 236 | 85 (59–235) | 55 (25–125) | 17 (3–38) | |

CISH | Morrison85 | 437 | 70 (46–370) | 68 (10–765) | 22 (10–120) |

Kim86 | 231 | 176.1 ± 55.1 | 152 ± 86 | 168 |

LSH, laparoscopic subtotal hysterectomy; CISH, classic intrafascial supracervical hysterectomy; ORT, operative time; EBL, estimated blood loss; LOS, length of stay.

Table 2. Comparison of early and late complications of laparoscopic subtotal hysterectomy and classic intrafascial supracervical hysterectomy procedures from selected studies

Early complications | Late complications | ||||||||

Procedure | Author | No. patients | Bladder injury | Febrile morbidity | Bleeding | Conversion | Return to OR | Cyclic bleeding | Cervix removal |

LSH | Donnez83 | 500 | 3 (0.6%) | 6* (2.4%) | |||||

Lyons84 | 236 | 1 (<1%) | 1 (0.4%) | 3 (1.3%) | |||||

CISH | Morrison85 | 437 | 3 (0.7%) | 3 | 1 (0.2%) | 4 (0.9%) | 1 (0.2) | ||

Kim et al86 | 231 | 1 (0.4%) | 3 (1.3%) | ||||||

LSH, laparoscopic subtotal hysterectomy; CISH, classical intrafascial hysterectomy; OR, operating room.

*Of 243 patients who were followed.

Hasson reviewed 50 consecutive LSH cases he had performed to assess quality-of-life outcomes after the procedure.87 Estimated blood loss was based on decrease in hemoglobin and hematocrit rather than the less reliable subjective estimates. The mean decrease in hemoglobin was 1.9 g (range, 0–6 g), and the mean decrease in hematocrit was 5.9% (range, 2–17%). Mean hospital stay was 1.2 days (nine patients stayed 2 days). Immediate complications included one bladder injury repaired laparoscopically, one pneumothorax in a patient with history of catamenial endometriosis, one patient with urinary retention, and one patient with occult inferior epigastric hematoma who received 2 units of packed red blood cells postoperatively. One patient experienced recurrent cyclic bleeding that did not require further treatment. The overall satisfaction rate was 94%, with one patient dead and two lost to follow-up: 89% of the patients were completely satisfied, 4% were satisfied, and one was satisfied with exception (cyclic vaginal spotting). The mean satisfaction score was 9.9 out of 10. Of all patients, 80% returned to work part-time within 2 weeks and 90% within 3 weeks; 58% returned to work full-time within 2 weeks, 78% within 3 weeks, and 94% within 1 month. According to 38 responses, sexual activity was resumed in a mean time of 27 days (range, 10–60 days), with 72% of respondents having sexual relations within 1 month and 91% within 6 weeks.87

Other investigators reported higher rates of late complications that necessitated removal of the cervical stump. Okaro and colleagues88 reported 16 cervicectomies after 70 LSH procedures for a rate of 22.8%. Pelvic pain (75%) and cyclic bleeding (44%) were the most common indications. The pathology report showed normal cervix in six patients (35%), chronic cervicitis in one (6%), residual endometrium in four (23.5%), and endometriosis in four (23.5%). One patient had cervical dysplasia, and another had mucocele. Incomplete removal of the lower uterine segment and the presence of endometriosis accounted for almost 50% of the cases.88

CONCLUSIONS

In selected cases, laparoscopic subtotal (supracervical) hysterectomy is a suitable alternative to total vaginal, abdominal, or laparoscopic hysterectomy for the treatment of benign gynecologic disease. Development of carcinoma in the cervical stump may be prevented in present times with periodic cytologic screening, and in the future with vaccination. Incomplete removal of the lower uterine segment and the presence of endometriosis may be associated with cyclic bleeding and pelvic pain, which may require further treatment. In expert hands and with well-selected patients, obesity should not be considered a contraindication for this approach.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

With eternal gratitude to Doctor Harrith Hasson for his constant encouragement. Gratitude also to Doctor Fernando Mahmoud for his review of the literature related to robotic surgery. Also, Ashley Barr for her assistance with the medical library.

REFERENCES

Farquhar CM, Sterner CA: Hysterectomy rates in the United States 1990–1997. Obstet Gynecol 2002;99:229-34. |

|

Wu JM, Wechter ME, Geller EJ, et al: Hysterectomy rates in the United States, 2003. Obstet Gynecol 2007;110:1091-5. |

|

Olive DL, Parker WH, Cooper JM, Levine RL: The AAGL classification system for laparoscopic hysterectomy. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc 2000;7:9-15. |

|

Lyons TL: Laparoscopic supracervical hysterectomy: A comparison of morbidity and mortality results with laparoscopic assisted vaginal hysterectomy. J Reprod Med 1998;38:763-7. |

|

Hasson HM, Rotman C, Rana N, Asakura H: Experience with laparoscopic hysterectomy. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc 1993;1:1-11. |

|

Donnez J, Smets M, Polet R, et al: LASH: Laparoscopic supracervical (subtotal) hysterectomy. Zentralbl Gynakol 1995;117:629-32. |

|

Metler L, Semm K, Lehmann-Wiellenbrrkl M, et al: Comparative evaluation of classical intrafascial supracervical hysterectomy (CISH) with transuterine mucosal resection as performed by pelviscopy and laparotomy, our first 200 cases. Surg Endosc 1995;9:418-23. |

|

Vietz PF, Ahn TS: A new approach to hysterectomy without colpotomy: Pelviscopic intrafascial hysterectomy. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1994;170:609-13. |

|

Sadoghi H: Supracervical uterus amputation via the vaginal route. Geburtshilfe Frauenheilkd 1994;54:602-5. |

|

Pelosi MA, Pelosi MA 3rd: Laparoscopic supracervical hysterectomy using a single umbilical puncture (minilaparoscopy). J Reprod Med 1992;37:777-84. |

|

Advincula AP, Song A: The role of robotic surgery in gynecology. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2007;19(4):331-6. |

|

Advincula AP: Surgical techniques: robot-assisted laparoscopic hysterectomy with the da Vinci surgical system. Int J Med Robot. 2006;2(4):305-11. |

|

Pitter MC, Anderson P, Blissett A, et al: Robotic-assisted gynaecological surgery - establishing training criteria; minimizing operative time and blood loss. Int J Med Robot. 2008;4(2):114-20. |

|

Stern E, Misczynski M, Greenland S, et al: Pap testing and hysterectomy prevalence: A survey of communities with high and low cervical cancer rates. Am J Epidemiol 1977;106:296-305. |

|

Carter B, Thomas WL, Parker RT: Adenocarcinoma of the cervix and of the cervical stump. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1949;57:37-51. |

|

Nielsen K: Carcinoma of the cervix following supracervical hysterectomy. Acta Radiol 1952;37:335-40. |

|

Papanicolaou GN: A new procedure for staining vaginal smears. Science 1942;95:438-9. |

|

Reich H, DeCaprio J, McGlynn F: Laparoscopic hysterectomy. J Gynecol Surg 1989;5:213-6. |

|

Robertson EA, de Block S: Decrease in the number of abdominal hysterectomies after introduction of laparoscopic hysterectomy. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc 2000;7:523-5. |

|

Härkki P, Kurki T, Sjöberg J, Tiitinen A: Safety aspects of laparoscopic hysterectomy. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2001;80:383-91 |

|

Novotny Z, Rojikoval V: Complications of laparoscopic-assisted vaginal hysterectomy, a 1996 survey of the Czech Republic. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc 1999;6:459-62 |

|

Wood C, Maher P, Hill D: The declining place of abdominal hysterectomy in Australia. Gynaecol Endosc 1997;6:257-60. |

|

Gimbel H, Settnes A, Tabor A: Hysterectomy on benign indications in Denmark 1988-1998 a register based trend analysis. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2001;80:267-72. |

|

American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology: Alternatives to hysterectomy in the management of leiomyomas. ACOG Practice Bulletin, number 96, August 2008. |

|

American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology: Endometrial ablation. ACOG Practice Bulletin, number 81, May 2007. |

|

ACS: ACS guidelines for early detection of cancer. Available at: http://www.cancer.org/docroot/PED/content/PED_2_3X_ACS_Cancer_Detection_Guidelines_36.asp?sitearea=PED. Retrieved Otober 20, 2008. |

|

American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology: Cervical cytology screening. ACOG Practice Bulletin, number 45, August 2003 |

|

U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for cervical cancer. Available at http://ahrq.gov/clinic/3rduspstf/cervcanwh.pdf. January 2003. Retrieved October 23, 2008 |

|

Storm HH, Clemmensen IH, Manders T, Brinton LA: Supracervical uterine amputation in Denmark 1978–1988 and risk of cancer. Gynecol Oncol 1992;45:198-201. |

|

Kilkku P, Gronroos M: Preoperative electrocoagulation of the endocervical mucosa and later carcinoma of the cervical stump. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 1982;61:265-7. |

|

Fox JF, Remington P, Layde P, et al: The effect of hysterectomy on the risk of an abnormal screening Papanicolaou test result. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1999;180:1104-9. |

|

Hasson HM: Cervical removal at hysterectomy for benign disease: Risks and benefits. J Reprod Med 1993;38:781-90. |

|

Hellström AC, Sigurjonson T, Pettersson F: Carcinoma of the cervical stump: The Radiumhemmet series 1959–1987: Treatment and prognosis. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2001;80:152-7. |

|

Hannoun-Levi JM, Peiffert D, Hoffstetter S, et al: Carcinoma of the cervical stump: Retrospective analysis of 77 cases. Radiother Oncol 1997;43:147-53. |

|

Forbes C, Jepson R, Martin-Hirsch P: Interventions targeted at women to encourage the uptake of cervical screening. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews Issue 1:2002. |

|

Ylitalo N, Sorensen P, Josefsson AM, et al: Consistent high viral load of human papilloma virus 16 and risk of cervical carcinoma in situ: A nested case-control study. Lancet 2000;355:2194-8. |

|

Josefson AM, Magnusson PK, Ylitalo N, et al: Viral load of human papilloma virus 16 as a determinant for the development of cervical carcinoma in situ: A nested case-control study. Lancet 2000;355:2189-93. |

|

Kalogirou D, Antoniou G, Karakitsos P, et al: Vaginal intraepithelial neoplasia (VAIN) following hysterectomy in patients treated for carcinoma in situ of the cervix. Eur J Gynaecol Oncol 1997;18:188-91. |

|

vanBeurden M, ten Kate FW, Tjong-A-hung SP, et al: Human papillomavirus DNA in multicentric vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia. Int J Gynecol Pathol 1998;17:12-6. |

|

Sugase M, Matsukura T: Distinct manifestations of human papillomaviruses in vagina. Int J Cancer 1997;72:412-5. |

|

Hasson HM, Parker WH: Prevention and management of urinary tract injury in laparoscopic surgery. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc 1998;5:99-112. |

|

Daling JR, Madeleine MM, Godefroy L, et al:Human papilloma virus, smoking, and sexual practices in the etiology of anal cancer. Cancer 2004;101:270-80. |

|

Trimble CL, Hildesheim A, Brinton LA, et al: Heterogeneous etiology of squamous carcinoma of the vulva. Obstet Gynecol 1996;87:59-64. |

|

Hoffman MS, Roberts WS, LaPolla JP, et al: Neoplasia in vaginal cuff epithelial inclusion cysts after hysterectomy. J Reprod Med 1989;34:412-4. |

|

Daling JR, Madelaine MM, Johnson LG, et al: Human papillomavirus, smoking, and sexual practices in the etiology of anal cancer. Cancer 2004;101:270-80. |

|

Trimble CL, Hildesheim A, Brinton LA, et al: Heterogeneous etiology of squamous carcinoma of the vulva. Obstet Gynecol 1996;87:59-64. |

|

ACS: American Cancer Society guideline for Human Papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine use to prevent cervical cancer and its precursors. Available at: hppt://caonline.amcancersoc.org/cgi/reprint/57/1/7. Retrieved October 1, 2008. |

|

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Quadrivalent Human Papillomavirus Vaccine. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/rr5602a1.htm. Retrieved september 19, 2008. |

|

Munoz N, Bosch FX, de Sanjose S, et al: Epidemiologic classification of Human Papillomavirus Types associated with cervical cancer. N Engl J Med 2003;348:518-27. |

|

Munoz N, Castellsague X, Berrington A, et al: Chapter 1: HPV in the etiology of human cancer. Vaccine 24S3 (2006) S3/1-S3/10. |

|

Moscicki AB, Schiffman M, Kjaer S, et al. Updating the natural history of HPV and anogenital cancer. Vaccine 2006;24:S42—S51. |

|

Datta DS, Koutsky L, Ratelle S, et al: Type-specific high risk human papillomavirus prevalence in the US: HPV Sentinel Surveillance Project, 2003-2005 [Abstract 1084]. Infectious Disease Society of America. Toronto 2006. |

|

ACS: American cancer Society cancer facts & figures 2008. Available at: http://www.cancer.org/downloads/STT/2008CAFFfinalsecured.pdf. Accessed September 23, 2008. |

|

Hildesheim A, Hadjimichael O, Schwartz P, et al: Risk factors for rapid-onset cervical cancer. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1999;180:571-7. |

|

Prescribing information for GARDASIL. Whitehouse Station (NJ): Merck & Co., Inc.; 2006. Available at: www.merck.com/product/usa/pi_circulars/g/gardasil/gardasil_pi.pdf . Retrieved september 23, 2008. |

|

Thakar R, Ayers S, Clarkson P, et al: Outcomes after total versus subtotal abdominal hysterectomy. N Engl J Med 2002;347:1318-25. |

|

Romanes GJ: 1981, Cunningham’s Text Book of Anatomy. Oxford, Oxford University Press. pp 571-572. |

|

DeLancey JO: Anatomic aspects of vaginal eversion after hysterectomy. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1992;166:1717-24. |

|

Baggish MS, Karram MM: 2006, Atlas of Pelvic Anatomy and Gynecologic Surgery. Philadelphia, Pa: Saunders, Elsevier. Anatomy of the vagina, pp 530. |

|

Baggish MS, Karram MM: 2006, Atlas of Pelvic Anatomy and Gynecologic Surgery. Philadelphia, Pa: Saunders, Elsevier. Anatomy of the cervix, pp 478. |

|

Mundy AR: An anatomical explanation for bladder dysfunction following rectal and uterine surgery. Br J Urol 1982;54:501-4. |

|

Baggish MS, Karram MM: 2006, Atlas of Pelvic Anatomy and Gynecologic Surgery. Philadelphia, Pa: Saunders, Elsevier. Identifying and avoiding urethral injury, pp 378. |

|

Hurd WW, Chee SS, Gallagher KL, et al: Location of the ureters in relation to the uterine cervix by computed tomography. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2001;184:336-9. |

|

Nezhat CH, Nezhat F, Seidman D, Nezhat C: Vaginal vault evisceration after total laparoscopic hysterectomy. Obstet Gynecol 1996;87:868-70. |

|

Jewett JF: Vaginal length and incidence of dyspareunia following total abdominal hysterectomy. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1952;63:400-7. |

|

Piacenza JM, Salsano F: Post-hysterectomy fallopian tube prolapse. Eur J Obstet Gynaecol Reprod Biol 2001;98:253-5. |

|

Prior A, Stanley K, Smith AR, Read NW: Effect of the hysterectomy on anorectal and urethrovesical physiology. Gut 1992;33:264-7. |

|

Kilkku P, Hivornen T, Gronroos M: Supra-vaginal uterine amputation vs. abdominal hysterectomy: The effects on urinary symptoms with special reference to pollakisuria, nocturia and dysuria. Maturitas 1981;3:197-204. |

|

Parys BT, Haylen BT, Hutton JL, Parsons KF: Urodynamic evaluation of lower urinary tract function in relation to total hysterectomy. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol 1990;30:161-5. |

|

Johns A: Supracervical versus total hysterectomy. Clin Obstet Gynecol 1997;40:903-13. |

|

Kilkku P: Supravaginal uterine amputation vs. hysterectomy: Effects on coital frequency and dyspareunia. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 1983;62:141-5. |

|

Kilkku P, Gronroos M, Hivornen T, Rauramo L: Supravaginal uterine amputation vs. hysterectomy: Effects on libido and orgasm. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 1983;62:147-52. |

|

Popov I, Stoikov S, Boiadzhieva M, Khristova P: Disorders in sexual function following hysterectomy. Akush Ginekol 1998;37:38-41. |

|

Strauss B, Jakel I, Koch-Dorfler M, et al: Psychiatric and sexual sequelae of hysterectomy, a comparison of different surgical methods. Geburtshilfe Frauenheilkunde 1996;56:473-81. |

|

Scott JR, Sharp HT, Dodson MK, et al: Subtotal hysterectomy in modern gynecology: A decision analysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1997;176:1186-92. |

|

Grimes DA: Role of the cervix in sexual response: Evidence for and against. Clin Obstet Gynecol 1999;42:972-8 |

|

Kuppermann M, Summitt Jr RL, Varner RE, et al: Sexual functioning after total compared with supracervical hysterectomy: A randomized trial. Obstet Gynecol 2005;105:1309-18. |

|

Dennerstein L, Wood C, Burrows GD: Sexual response following hysterectomy and oopherectomy. Obstet Gynecol 1997;49:92-6. |

|

Hedley AA, Ogden CL, Johnson CL, et al: Prevalence of overweight and obesity among US children, adolescents, and adults, 1999-2002. JAMA 2004;291:2847-50. |

|

O’Hanlan KA, Lopez L, Dibble SL, et al: Total laparoscopic hysterectomy: body mass index and outcomes. Obstet Gynecol 2003;102:1384-92. |

|

Heinberg EM, Crawford III BL, Weitzen SH, et al: Total laparoscopic hysterectomy in obese versus nonobese patients. Obstet Gynecol 2004;103:674-80. |

|

Hasson HM: Laparoscopic cannula cone with means for cannula stabilization and wound closure. J Am Assoc Gynocol Laparosc 2001;5:183-5. |

|

Donnez J, Nisolle M, Smets M, et al: Laparoscopic supracervical (subtotal) hysterectomy: A first series of 500 cases. Gynaecol Endosc 1997;6:73-8. |

|

Lyons TL: Laparoscopic supracervical hysterectomy. Baillieres Clin Obstet Gynaecol 1997;11:167-79. |

|

Morrison JE Jr, Jacobs VR: 437 Classic intrafascial supracervical hysterectomies in 8 years. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc 2001;8:558-67. |

|

Kim DH, Bae DH, Hur M, Kim SH: Comparison of classic intrafascial supracervical hysterectomy with totallaparoscopic and laparoscopic-assisted vaginal hysterectomy. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc 1998;5:253-60. |

|

Hasson HM: Quality of life after supracervical laparoscopic hysterectomy. J Am Assoc Gynocol Laparosc 2001;8(3 suppl):S24. |

|

Okaro EO, Jones KD, Sutton C: Long term outcome following laparoscopic supracervical hysterectomy. Bjog 2001;108:1017-20. |